A dreamer of pictures

I run in the night

You see us together,

chasing the moonlight,

My cinnamon girl.

Cinnamon Girl. Neil Young.

As you may have read, each week the avant guardian asks its contributors to write on a changing theme. This has the benefit for the contributors of eliciting novel responses and the total result approaches an exquisite corpse. Given this format I attempt with each installment of popOp to follow this surrealist experiment and palpate what I think Nicolas Bourriaud calls relational aesthetics. As Claire Bishop points out, the next logical question after highlighting sociality/relationality in art practice is to discuss what kinds of relationships are being formed?

Being a student of Jacques Rancière and a working sociologist; I, like Bishop, am simpatico with Bourriaud’s ideas, but would also like some more meat on the bones of this thinking. This is why popOp tends to write about spectacular agency, a phrase I’m cobbling together from Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and Giorgio Agamben’s What Is an Apparatus?

Given that the interwebz are a visual media, however, it’s really tedious and torturous to read plodding, sprawling academic texts about esoteric thinking. So, with each installation of popOp I try to include a dose of contemporary artworks, some lyrics to songs, and a little explication of where some of that obtuse philosophy intersects with celebrity (as in the case of Lil’ Wayne or Sasha Grey).

I think this format popOp has taken finds close similarities, then, to the recent exhibitions of Saâdane Afif (exhibiting in the French Pavillion at the Shanghai World Expo). The most obvious parallel would be found in his Lyrics project which then became Technical Specifications at Witte de With in Rotterdam two years ago. Briefly, Afif asked writers to generate text based on his artworks, then he asked bands to make music with these texts as lyrics; thus there is a filtering of a filtering. Adding yet another layer, Afif then reinterprets his works in light of these interpretations.

Afif is accomplishing something alchemical in doing this: he’s transfiguring sound into sculpture. The transmutation becomes more clear with a little video (now, can we add the vuvuzela sound to it?)

Let’s kinda trace-out the movement here:

- the work begins as a conception that Afif enacts (certainly not ex nihilo, a problem that might be the source of his method)

- the materialized work is then observed and understood/translated by the viewer

- Afif asks particular viewers to translate (their reception of) the materialized work into text

- this text is then translated into lyrics with music

- in the case of the above videos from Afif’s Duchamp Prize-winning Vice de Formes: In Search of Melodies (at Galerie Michel Rein) the live performance of the music by Louis-Philippe Scoufaras is then recorded by a machine and the piece is played ad infinitum.

- in the case of Technical Specifications the performance never ends on the website www.technicalspecifications.net

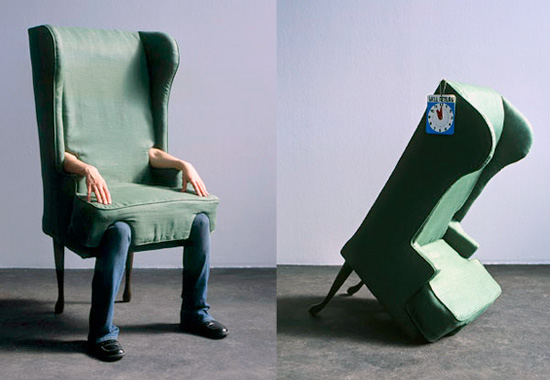

I want to emphasize the movement of the works because it allows us to also introduce Jamie Isenstein‘s image at the top of this post. Both artists, it would seem, are engaging not only issues of time but are also illuminating the possibility of desubjectification, a term I’m still working-through.

In Isenstein’s work, time’s role is essential to the truthiness and ensuing gallows humor. Her work, like Afif’s, requires the viewer to go expand their understanding of sculpture as well as performance art. Isenstein’s “WILL RETURN” signs highlight the central problematic of performance art: unlike a painting or a marble bust, the piece ceases to exist when the performer is not present. Hanging these shopkeeper signs allows the viewer a kind of calavera catrina laugh; and let me point out that it is not unheard of to die from laughing. We laugh in part because we know that Isenstein, like birthdays, will return, but only so many times.

The shame of laughing at death is not because we find humor in the act of dying but the shame is in denying that death will come to us all and so obsessing and fixating on maintaining an illusory control on the act of living. As someone smarter than me pointed-out recently, no matter how much money Bill Gates has, he cannot hire someone to do his dying for him.

While Isenstein plays with pursuit of immortality in her works, Afif points to the possibility of immortality through cultural transmission: one person builds on their understanding of another person, builds on another (mis)understanding, and so on. Both artists ultimately are re-presenting the fundamental interrelatedness of being, and are thus beseeching the viewer to re-investigate their place in the socius.

Foucault described desubjectivity as an affirmation of identity, but not the identity that is fixed and ascribed only by one’s relationship to power. His notion is much closer, it seems, to the machinic assemblages that Deleuze & Guattari outlined. “Who I am” is the site of inscription of the coding of the predominant power structures, but “who I am” is also the composition of a constellation. To use Todd May’s example: my bicycle (a technical machine), when attached to “who I am” is a vehicle (and now “who I am” can be expressed “who I am”+bicylce”), “who I am”+bicycle go to the art gallery (an art displaying machine) and if I leave my bicycle inside the gallery the bicycle becomes an art machine. Desubjectification is not the process of losing a concrete self, but an affirmation of the possibility of being able to combine, perhaps like Whitman in Song of Myself.

In addition to the obvious engagement with Clement Greenberg‘s Towards a Newer Laocoon (1940), which is an engagement with Lessing’s Laocoon: An essay upon the limits of painting and poetry (1766) Saâdane Afif offers Laocoon (2005):

Afif’s Laocoon is literally a body without organs (BwO). As Deleuze & Guattari described in their Anti-Oedipus, the body without organs appropriates desiring production (the natural tendency of being human is to develop desire-as-production in the same way a bricoleur cobbles together solutions to their problems) and the BwO, “serves as a surface for the recording of the entire process of production of desire so that desiring-machines seem to emanate from it in the apparent objective movement that establishes a relationship between the machines and the body without organs” (AO, 11; emphasis mine). As such, the ethical imperative, it would seem, is for the artist, the viewer, and the hosting gallery to follow Foucault’s injunction in the Preface to Anti-Oedipus: to use this philosophy to engender non-fascist living.

I don’t know if that’s possible. The Palais de Tokyo, Bourriaud’s gallery in Paris and frequent site for Afif’s work, do attempt to be transparent in who presents there, how many people visit, and they do provide a host of docents to accompany visitors and facilitate an understanding of contemporary art practices.

Images:

boldongrey, Witte de With, ffffound!, antidote 2006 & Galeries lafayette